Castello di Brescia

Perched at the top of the Cidneo Hill, the Castle is one of the most fascinating fortified complexes in Europe, still bearing the traces of the various dominations of the past.

The Mastio, the fortified keep on the top of the hill, with its mighty Torre dei Prigionieri (Tower of the Prisoners), the drawbridge and the Mirabella Tower, the last trace of the church of Santo Stefano in Arce overlooking the town, bear witness to the communal period and the Visconti domination. The imposing bastions, with their monumental gate, are testaments to the power of the Republic of Venice – La Serenissima – that ruled the city for about four centuries.

Within its walls, the Castle also houses two museums: the Luigi Marzoli Arms and Armor Museum and the Museum of the Risorgimento Lioness of Italy.

The Castle

The Castle is home to charming and little-known passages, atmospheres infused with mystery, affording sweeping views over the city, stretching from the Ronchi slopes and the Brescian valleys to the Apennines and the Alps.

Stage to many key events in the history of Brescia, including its famous Dieci giornate (Ten days), the Castle is today one of Brescia’s most evocative sites, where several elements coexist: evidence of the Roman era, such as the oil warehouses with their Botticino stone tubs, medieval constructions, and a 1909 locomotive, displayed to the delight of younger visitors inside the “Falcone d’Italia” (the Falcon of Italy, one of the Castle’s names).

The Ten days of Brescia

In the most delicate passage of the Risorgimento epic, 1848, the people of Brescia organized an underground committee headed by patriot Tito Speri and the curate of Serle Don Pietro Boifava. It was the news of the Austrians’ planned collection of a hefty fine imposed on the citizenry after the formation in 1848 of a Provisional Government that sparked the collective rebellion against the Hapsburg rulers on March 23, 1849. The spark was also ignited by the conflicting rumors coming from the front, in the second phase of the First War of independence (1848-1849), declared by Charles Albert, King of Sardinia, in an attempt to regain, after the events of 1848 freeing it from the Austrians. In fact, misleading reports of victory for the Savoy troops arrived, mixed with royal dispatches about the Piedmontese defeat at Novara (March 23, 1849), which was followed by the abdication of Charles Albert and the signing of the armistice of Vignale (March 24, 1849) between the new king, Victor Emmanuel II, and General Radetzky.

Brescia, which rose up trusting in Piedmontese help, chose not to surrender to the Austrians, engaging in resistance for ten very long days, with the involvement of the people, who fought strenuously house by house and behind barricades set up at key points in the city, while the Austrians, entrenched in the Castle, bombarded the urban perimeter. The entire city became a theater of war: the city’s bell towers and towers were used as lookouts and as a base of operations for sharpshooters. Also targeted by Hapsburg shells were the most emblematic symbols of the municipality, such as the Loggia, in which the hole caused by an Austrian shell fired from the Castle still remains, at the base of one of the walls of the Vanvitellian Hall. The insurgents, also led by Tito Speri, faced the Austrians in every corner of the city. Barricades were erected at Porta Torrelunga, Contrada San Barnaba, Contrada Sant’Urbano and many other places. The Brescians also engaged in violent clashes with the Austrians on the Ronchi and at Sant’Eufemia della Fonte.

The surrender of the Brescian people did not occur until April 1, 1849, after Marshal Haynau had rushed to support the Austrian garrison barricaded in the Castle. On the night of March 31, in fact, taking advantage of the Strada del Soccorso, a secret and still existing safe-conduct connecting the top of the Castle to the city, new armed garrisons led by Haynau managed to reach the Cidneo hill. The insurrection was snuffed out in blood, with violent repression especially against civilians, who were bent by shootings that lasted until August 12, the date of the amnesty desired by Radetzky. Insurgents taken prisoner were locked up in the Castle or in the prison of St. Urban and many of them were shot. Impatience with the Austrian rulers, however, was not abated, so much so that Tito Speri animated a new clandestine insurrectionary committee, a decision that would cost him his life. He was hanged in Belfiore, Mantua, in 1853.

The lion-like courage with which Brescia fought during the Risorgimento earned the city the title of Leonessa d’Italia, Lioness of Italy, coined by Aleardo Aleardi and taken up by Giosue Carducci in his Odi Barbare, Book V, a composition from May 1877, closing with these famous verses:

Rejoicing in the event Brescia received me,

Brescia the strong, Brescia the iron-handed,

Drenched in the blood of her enemies,

Brescia the lioness of Italy.

Historic phases of the Castle of Brescia

–From geological formation to the first prehistoric settlements

The summit of the Cidneo Hill is the earliest Brescian settlement. The oldest finds unearthed during excavations date back to the Iron Age.

–Celtic settlement

The earliest significant anthropization of the hilltop area dates back to this period, when the Celtic populations, the Ligurians at first and then the Cenomani, used it as a place of worship, perhaps dedicated to the god Bergimus.

–Roman period

During the Roman period the hill continued to be used as a place of worship. Temples of uncertain dedication were erected whose steps are still visible inside the Weapons Museum.

Below the temple are oil warehouses and other containers whose function remains unknown to this day. Other oil warehouses were built underneath the grassy expanse today known as the Mirabella lawn.

–Late Antiquity and the Longobard period

The basement of the so-called Mirabella Tower probably dates back to the late Imperial Age. An early Christian martyrium has been found, attesting the perpetration of the site’s spiritual vocation even in the Christian period.

After the sackings of the Visigoths, Huns, and Heruli, came a period of Ostrogothic occupation, of which very few documentary and material traces remain but which was very important for the town. Then came the Longobards, who for the first time used the hill for defensive purposes, building the first castrum.

–Late Middle Ages (twelfth–fourteenth century)

In the late Middle Ages, in continuity with the hill’s cultic vocation, a number of churches were built, the most important of which was the church of Santo Stefano in Arce, whose entire lawn-covered base and some elevated structures, including one of the two bell towers (the Mirabella Tower), are still preserved.

Construction of the Mastio also began at this time.

–Visconti and Malatesta periods

During the rule of the Visconti family the fortification works were rationalised by taking down old buildings and erecting the Mastio above the old Roman temple and oil warehouses. These works were required by Luchino Visconti and his brother Giovanni, who also commissioned the frescoes that are still visible today.

–First Venetian domination

The Venetian domination is characterised by important works to modernise the fortified structures, starting from the transformation of an old quadrangular Visconti tower into a more modern round tower, the Torre dei Prigionieri (Tower of the Prisoners). Thanks to the work of Giacomo Coltrino, a new tower known as Torre Coltrina was built to replace an old one that had collapsed.

–French period

The short-lived French occupation was particularly significant for the Castle of Brescia, since the new rulers’ defensive necessities led them to lay out a state-of-the-art fortification system, specifically called Torre dei Francesi (Tower of the French), below the Mirabella lawn.

–Venetian rule and the Napoleonic period

It was with the return of the Venetian rule that the Castle underwent its most significant development, with the construction of a new walled enclosure, the widening of the Strada del Soccorso and the construction of the San Pietro, San Marco, San Faustino and Pusterla bastions. The fortress was also equipped with numerous embrasures and gunports, buildings for storing provisions (the Grande Miglio), ovens, barracks, religious buildings, cisterns, artillery stores (the Piccolo Miglio) and armouries.

–Napoleonic and Austrian periods

During the Napoleonic period, the Castle, which had been in decline for some time, remained unchanged and was used mainly as a prison.

With the transition from French to Austrian occupation, the Castle took on new strategic functions. The Austrian structures concentrated on re-functionalizing the buildings and military barracks, giving the Castle the form of large barracks. The Mastio area, on the other hand, was abandoned.

–Kingdom of Italy

In 1859 Brescia became part of the new-born Kingdom of Italy. The Castle, taking advantage of the Austrian structures, continued to be used as barracks for the Italian troops. The Mastio was used as a military prison. In the years between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, thanks to the initiative of Captain Sorellli, restoration work began on the oldest and most precarious buildings, using the inmates of the Mastio as workforce.

In the twentieth century, the Castle made its debut as a public park with the 1904 Expo..

During World War I, some of the Castle’s structures were used for the detention of Austrian prisoners, before going back to being an urban space between the two world wars.

-1943-1945

The Castle’s function as a city park from the twentieth century to the present day saw a dramatic re-functionalization during the Italian Social Republic, becoming barracks for the Fascist and German militias, while a few buildings were used as political prisons.

–From the Post-War period to the present day

The Castle has become one of the most loved places by the people of Brescia, who can finally enjoy its interiors. Over the course of the twentieth century there have been numerous redevelopment projects, starting with the arrangement of the zoo in place of the Venetian barracks, which were demolished and removed in the 1980s.

The Museums of the Castle

“Luigi Marzoli” Arms Museum

Inside the fourteenth-century Mastio Visconteo, the Luigi Marzoli Arms Museum houses one of Europe’s finest collections of antique armour and weapons, displaying Brescia’s time-honoured weaponry tradition, documenting its technological and artistic evolution between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries.

Museum of the Risorgimento Lioness of Italy

The Museo del Risorgimento Leonessa d’Italia reopens its doors for the first time in 20 years in the Grande Miglio of the Castle with an innovative and immersive layout

The result of long historiographical and design work, this new exhibition recounts the Risorgimento as a phenomenon of European relevance and of pressing topicality. Paintings, sculptures, heirlooms and “relics”, having undergone careful restorations, are showcased as material manifestations of a long and complex history that culminated in Italian Unification. A rich digital collection accompanies and integrates a storytelling that reaches up to the present day, involving the visitor in the events that saw Brescia at the centre of the long Risorgimento, making it famous throughout the world as the Lioness of Italy.

The route embodies a new concept of historical museums, in which storytelling plays a leading role and takes the audience on a journey from the Risorgimento to current events. The museum alternates local and European scale, narrative and analysis, objects and digital collections, with the aim of illustrating events, places, and protagonists of the Italian Risorgimento in an innovative and participatory way. The exhibition consists of eight sections and is entirely narrated in both Italian and English.

Castle 360°

Information

Pricing

Access to the Castle area is free and open.

The visit inside the fortress is allowed only by purchasing the ticket for the Museo delle Armi Luigi Marzoli and the Museum of the Risorgimento Lioness of Italy.

Opening times

The Castle of Brescia is open every day, 365 days a year.

Opening hours may vary in case of events.

Infopoint

The Infopoint is the Castle’s tourist information point.

For information:

castello@bresciamusei.com

T. 030 8174400

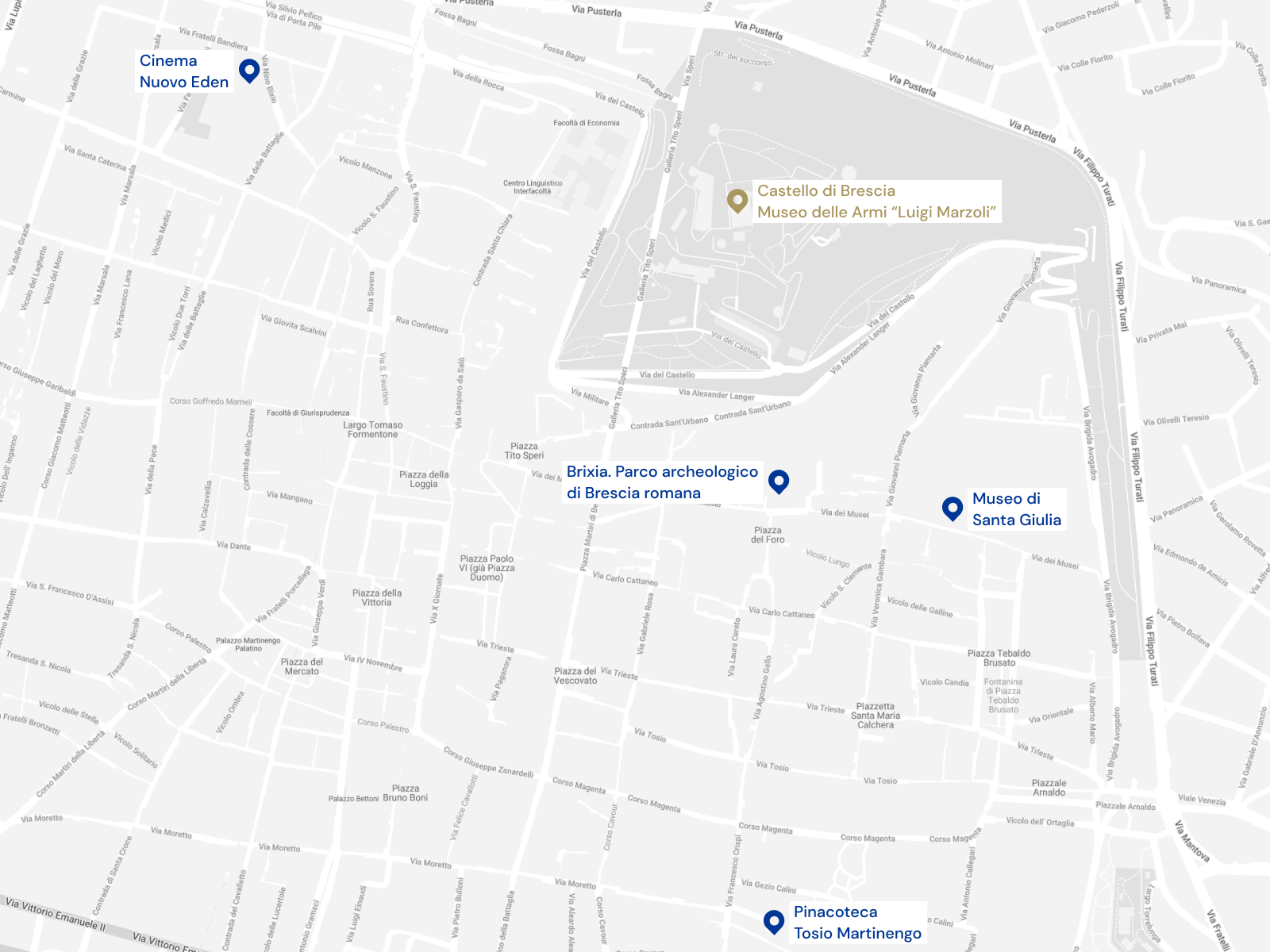

Getting here

Via Castello, 9 – Brescia

By Bus and subway

- by bus: check bus routes on the Brescia Mobilità website

- by subway: San Faustino stop + a 10-minute walk /Piazza Vittoria stop + a 15-minute walk

By Taxi

Radio Taxi Brixia

tel. (+39) 030.35111

Car parking

Along the road that leads to the Castle there are several free and pay parking areas, also for people with disabilities.

Bicimia

Go to the Brescia Mobilità website to discover this bike service

By Train

Reach us by train, then from Brescia Train Station:

- on foot: 20-minute walk, direction Castello

- by subway: San Faustino stop + 10-minute walk / Vittoria stop + 15-minute walk

By Plane

Aeroporto Gabriele D’Annunzio Brescia Airport

(20 Km from Brescia)

Orio Al Serio Bergamo Airport

(56 Km from Brescia)

Valerio Catullo Verona Airport

(70 Km from Brescia)

Publications

No results available